The world’s safest asset is no longer…

By Alexandre Hezez, Group Strategist

Editorial

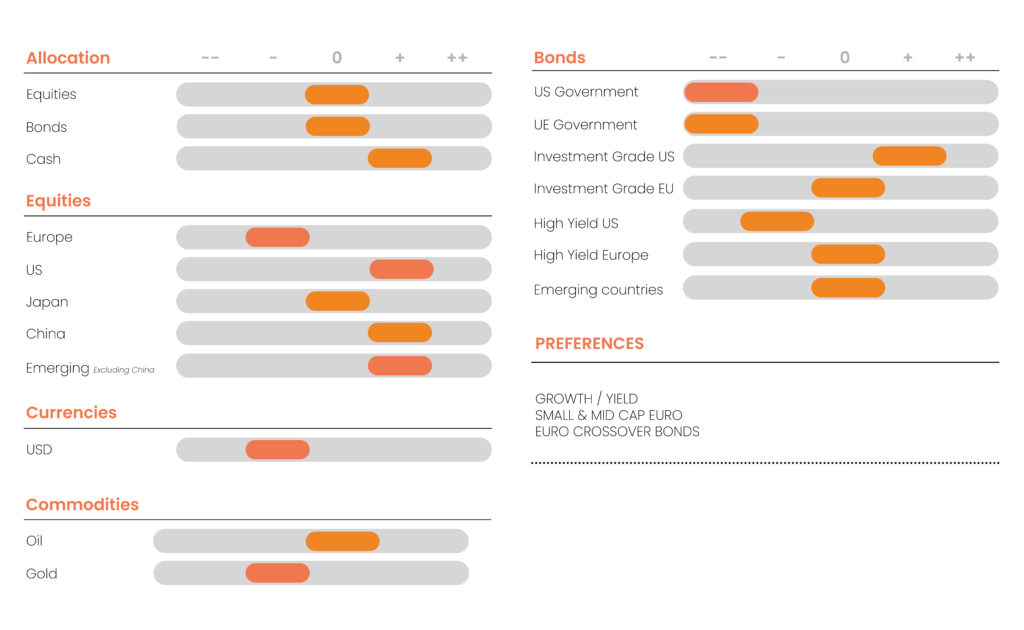

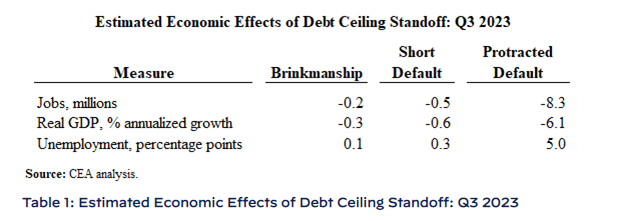

The U.S. President returned from the G7 summit in Japan ahead of schedule in order to break the impasse over the federal debt. The summit was of great importance given the economic and geopolitical context, but the top priority remains domestic politics and the debt issue, the consequences of which would range from “serious to catastrophic”, in the words of Bill Gates. For a “protracted default” scenario, the Council of Economic Advisors assumes “negative shocks to consumer and business confidence that mimic those that occurred during the Great Recession”.

Economic impact estimates by the Council of Economic Advisors

President Joe Biden and Republican Kevin McCarthy are stepping up their meetings at the White House to discuss raising the US debt ceiling. The two parties remain at odds over the budget cuts demanded by the Republicans as a condition for raising the ceiling. Leaving Japan, Joe Biden told reporters that the proposals from the Republicans, who control the House of Representatives, were“simply, quite frankly, unacceptable” and that it was time for the Republicans to accept that there was no bipartisan deal to be struck solely on their partisan terms. They need to move too.

On January 19, 2023, the Treasury announced a“period of suspension of debt issuance” and began using well-established“extraordinary measures” to borrow additional funds without exceeding the debt ceiling. Even if the situation has already been experienced, it remains complex this time around, as the polarization of political life in the United States has never been so strong. It should be noted that the United States has already experienced a trauma of this kind in 2011. Indeed, they were confronted with a political impasse in the negotiations to raise the debt ceiling. This ceiling sets the maximum amount of debt that the federal government is authorized to contract. Disagreements between political parties have created uncertainty about the ability of the United States to meet its debt payment obligations on time. This raised concerns about their financial credibility and led to a downgrading of their credit rating. In August 2011, Standard & Poor’s downgraded the US credit rating from AAA (the highest rating) to AA+, with a negative outlook. This deterioration already reflected concerns about the government’s ability to solve fiscal problems and reduce the budget deficit effectively.

Back in 1979, Republicans and Democrats were already squabbling over whether or not to raise the cap… Although they eventually reached a last-minute agreement, administrative errors prevented the compromise from being sealed in time. As a result, the United States was unable to meet its obligations for several days. This was the last time the country defaulted.

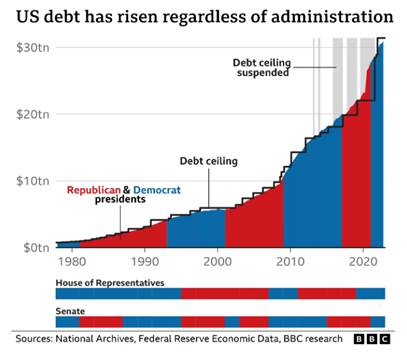

The debt ceiling

The U.S. debt ceiling is a spending limit set by Congress. Note that this ceiling does not exist anywhere else. In other countries, a budget is voted, and once the expenditure has been voted, you go into debt if the revenue doesn’t balance the expenditure. In the United States, we vote on a budget, which may include a deficit, and there is a debt ceiling that limits the amount of American debt. This mechanism has never, in itself, been a real limitation, as in all other countries.

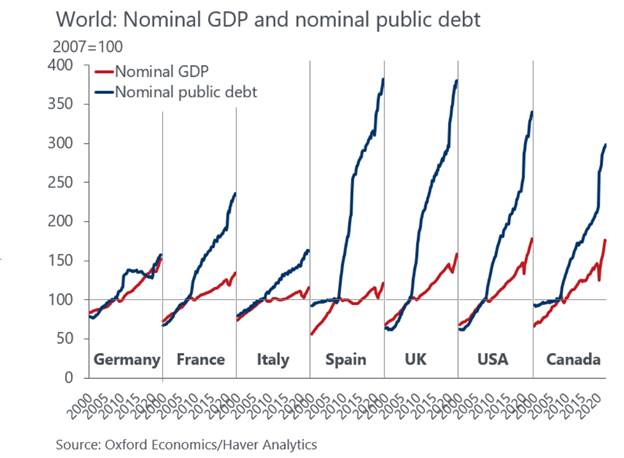

Debt versus GDP

But we must remember that this debt ceiling measure dates back to the 1914 war. It was introduced not to complicate but to facilitate the work of the US Treasury. Until then, he had to apply for the right to issue every debt, every bond, every debt security, and we wanted to make things easier for him by allowing him to issue, as long as it didn’t exceed a certain amount. This amount is the debt ceiling we inherited today.

Since the 1960s, the debt ceiling has been raised by Congress 78 times, and theuse of the debt ceiling by parliamentarians as a pressure tool to get the government to cut spending has only grown stronger.

History of US debt

The current situation

On December 16, 2021, lawmakers raised the debt limit by $2.5 trillion to $31.4 trillion. The debt ceiling of the world’s leading economy was reached in mid-January. Since then, the US Treasury has been using accounting tricks to delay the day when this threshold will be exceeded as long as possible. But the room for manoeuvre is shrinking.

Graph: US Treasury balance

If the cap is not raised above the current threshold by June, the US could default on its debt. This would mean that the government would no longer be able to borrow money or pay all its bills. Social security contributions and salaries for federal civil servants and military personnel could be suspended. This would also threaten the global economy.

If the debt limit is not raised or suspended before the Treasury runs out of cash and extraordinary measures, the government will have to delay payments for certain activities, default on its obligations, or both.

If the Treasury’s liquidity and extraordinary measures are sufficient to fund the government until June 15, the expected quarterly tax receipts and additional extraordinary measures will probably enable the government to continue funding its operations at least until the end of July. In this situation, the country will no longer be able to issue new loans to finance itself, and will no longer be able to pay its bills or its civil servants.

Political issues

In exchange for their support for raising the debt ceiling, Republicans are demanding budget cuts in the order of $4.5 billion, which means scuttling several of Mr. Biden’s legislative priorities. They are also calling for increased military spending and border security. Both President Biden and Mr. McCarthy are under pressure from the left and right of their respective parties to maintain their positions. This is not the first time that the threat of default has loomed over the United States. In fact, it’s been quite common since the debt ceiling became a real political tool on the other side of the Atlantic. The issue is now at the heart of negotiations between elected Democrats, who want to authorize an increase in the debt ceiling to avert the risk of default, and Republicans, who refuse to do so unless they obtain a commitment to significant cuts in public spending in return.

Kevin McCarthy, Speaker of the House of Representatives, was elected under very special conditions. He was elected after 14 votes from his party, because a section of Republicans is extreme and holds the president. Conditions have never been worse. We can expect situations for which we are not prepared : McCarthy is in a position of weakness that forces him to be tough with Joe Biden.

Let’s not forget that Donald Trump, who still has many supporters in Congress,has urged Republican elected officials to provoke a default unless they get “massive” budget cuts from Democrats, stoking tensions in Washington.

Compromise would be difficult to achieve, as Mr. Biden’s left-wing Democrats and Mr. McCarthy’s right-wing Republicans would regard any concession as a betrayal of fundamental political principles.

June as judge of the peace

Discussions in Washington remain tense and are continuing. The days are now numbered and no agreement has yet been reached. This situation is of concern to financial investors, who are aware of the risk of default on US debt and the need to halt a great deal of spending.

These discussions are still deadlocked around the same issues: the Republicans insist on reducing spending to its 2022 level, i.e. a $130 billion cut, which is still a problem for the Democrats.

A positive outcome should continue the relief movement that had begun, leading to a temporary rise in sovereign rates and risky assets, although this increase remains limited. It should be noted that even in the event of an agreement, the Fed will maintain the “pause” mentioned at its next meeting in June, unless there are major new surprises regarding employment and price data.

With Congress deadlocked and unable to vote to raise the debt ceiling to keep the government running, the government is considering the use of a controversial tool : section 4 of the 14th amendment. Added to the U.S. Constitution after the American Civil War in 1868, Article 4 of this amendment states that “the validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, shall not be questioned”. In other words: spending already voted on must be honored, whether or not the debt ceiling is exceeded (created at the time to prevent Southern legislators from sabotaging the American federal union by repudiating the federal debt created by the war). Even if it could be used in theory, not only would this tool open the door to a precedent whose consequences are unknown, but in practice it would take a long time to implement. In the past, other administrations, such as that of Barack Obama, have also considered recourse to the 14th Amendment, but deemed it unfeasible.

The economic consequences of default

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the United States could find itself into default as early as June if Republicans and Democrats fail to agree on raising the debt ceiling. However,“additional extraordinary measures” and end-of-quarter tax revenues could enable the government to“finance its operations until at least the end of July“. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-05/59130-Debt-Limit.pdf

Importantly,“if the debt ceiling is not raised or suspended, the Treasury would not be authorized to issue new debt, except to replace maturing or redeemed securities“. This would lead to payment delays for certain government activities, default on government debt bonds, or both.

The CBO adds that this situation could have serious consequences, such as difficulties in the credit markets, disruptions to economic activity and a rapid increase in borrowing rates for the Treasury.

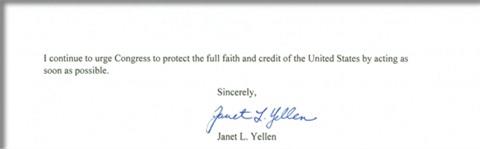

For Janet Yellen, the consequences of an American default would extend far beyond the borders of the United States: “There’s no good reason to create a crisis ourselves. A default on our debt would have such a major impact on the United States and the global economy that I think it should be regarded by all as unthinkable.“she declared.

Excerpt from Janet Yellen’s letter to Kevin McCarthy

Julie Kozack, Director of Communications at the International Monetary Fund, shares the same view. In her view,“a default on US debt would have very serious repercussions, not only for the United States, but also for the global economy“. Among these repercussions, she mentions higher interest rates, widespread instability and economic consequences.

Currently, in May, the country’s CDS (Credit Default Swap) is at an all-time high.

1-year CDS on US debt

Our default scenario

Controversial debates, such as the near-default of 2011, should serve as a cautionary tale, as the stock market ignored and then violently reassessed the risk of a US default (for example, in 2011, the S&P 500 fell 17% in two weeks).

S&P 500 and US 10-year yields

Why might 2023 be ” worse ” than 2011 for risk assets?

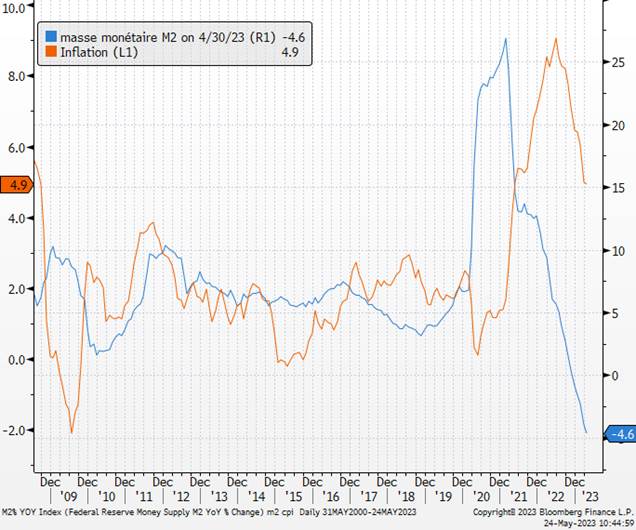

Putting aside differences in political context, the economic and market contrasts between today and 2011 are striking:

> phase of the business cycle

> monetary policy (restrictive or accommodating),

> money supply (collapsing or expanding),

> inflation (high or low),

> nominal and real interest rates (higher than in 2011),

> equity valuations

> the degree of concentration of indices

US money supply versus inflation

All these factors point to a stronger revaluation of risk today than in 2011, should the risk of default increase. The only mitigating factor was the absence of the European debt crisis, which was then an independent source of volatility.

The debt ceiling and federal spending have two major implications for investment:

1. The possibility of a violent “risk-off” move in equities as the deadline approaches without a widely supported resolution, and the possibility of federal spending cuts on Biden’s key legislative priorities (e.g., the IRA) following a partial/complete debt ceiling deal or federal budget negotiation in the fall of this year.

2. Although a downgrade could have an impact on the rating, Treasuries remain the highest-rated asset in the U.S. and, given rising political and economic uncertainty, should recover as risk aversion increases.

Anxious technical questions

Be that as it may, many questions are now being asked about US debt, considered the safest asset in the world, that were unthinkable just a few months ago!

Will money market funds be forced to liquidate Treasuries in the event of a technical default?

How will a technical default affect US government-backed securities?

Will the Federal Reserve accept defaulting Treasury securities as collateral at the discount window?

What will be the status of Treasury guarantees in the event of technical failure?

Will interest be charged on late payments?

Which Treasury securities are most likely to be affected by technical failure problems?

How will Ukraine be financed?

Joe Biden announces new assistance for Ukraine at G7 summit

Our scenario

Treasury securities andCredit Default Swaps (CDS) reacted more sharply to these growing risks, with CDS implying a technical default probability of around 4%.

Three scenarios are possible in the coming weeks:

1. A short-term compromise to postpone the issue for a few months, to allow more time for negotiation.

2. A compromise on raising the debt ceiling between Democrats and Republicans.

3. An absence of compromise, with the possibility for the US Treasury to “prioritize the payment of debts over the payment of current bills”. In that case, it’s likely that the US rating will be downgraded, which would be very bad news indeed.

We remain cautiously optimistic that the discussions between President Biden and Chairman McCarthy will result in an agreement, albeit partial, to raise/suspend the debt ceiling. However, as we approach the deadline, the risk that this time will be different, with a non-negligible probability of technical default, increases. The combination of a difficult political backdrop, an earlier-than-expected deadline, the lack of alternatives if Congress fails to act, and an optimistic equity stance suggests a higher risk to equities if the deadline passes without the debt ceiling being resolved.

Our basic assumption remains that the debt ceiling will eventually be lifted or suspended, although the path to this resolution may be last-minute and lead to market instability. We anticipate that a temporary or full agreement will have a negative impact on federal spending and will likely generate contentious budget negotiations later in the year.

Given the potentially short-term nature of raising the debt ceiling, there remains a risk of revisiting this issue in 2024. The political situation will be largely unchanged, but heightened market sensitivity due to its implications for the 2024 presidential election could exacerbate tensions once again.

After a first alert in 2011, this second episode will definitively cast doubt on the asset that was once considered the safest in the world.

CONVICTIONS

Many responses in June

We remain convinced of the attitude of central banks over the coming months:

The Fed is likely to pause (possibly after a maximum increase of a further 25 basis points).

Europe is set to continue its monetary tightening (25 basis point increase expected over the next three meetings).

Japan, for its part, has to start thinking about moving away from its ultra-accommodating policy.

China’s central bank will be faced with the challenge of navigating between a falling yuan and maintaining bank interest margins. The PBOC will have room to cut rates if the Federal Reserve decides to end its rate hike cycle.

Main central bank rates

The global economy remains resilient thanks to dynamic employment and consumption. The long-awaited recession is likely to be mild. The impact on corporate earnings is likely to remain low, as confirmed by recent first-quarter earnings releases. The level of liquidity in the portfolios should be reinvested at each fluctuation. The current level of interest rates now makes it possible to balance your portfolio in terms of risk between bonds and equities.

Given the expected steepening of the yield curves, linked to the expected end of aggressive monetary policies and the market’s gradual assumption that current levels (or even slightly higher) will be maintained over the long term, duration should be limited on credit (3 to 4 years).

As far as equities are concerned, we prefer growth stocks to those more sensitive to the economic cycle (such as the automotive sector). The financial sectors are likely to remain highly volatile, depending on news about US regional banks and the impact of the real estate downturn in Europe. We favor the major European systemic banks.

Against a backdrop of a gradual slowdown, sectors with sustained dividend growth are particularly well-suited.

In the United States, the reduction in credit supply caused by the US banking crisis has significantly increased the likelihood of a recession. The future effects of the unprecedented monetary tightening already underway must also be taken into account. We believe this recession should be moderate, as the high level of debt in the system would make any deep recession dangerous for the sustainability of that debt – a reality central banks are more than aware of. The fall in inflation should gradually allow real wages to rise. Debates over the debt ceiling are likely to cause high volatility across all assets, but we continue to anticipate a minimal agreement to maintain equilibrium until the next US elections. We believe that this could give a positive boost to the US market after the agreement.

Investors’ positions remain protected, as evidenced by the speculative positions on the S&P 500 reported by the CFTC. More than two months after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the situation is gradually easing in terms of stress indicators (Fed lending to financial institutions is slowly declining), but also on the credit and deposit fronts. For the latter, the slowdown observed over the last few months is continuing after a phase of great concern that proved to be temporary. The credit spigot is therefore not completely closed, and fears of a massive flight of deposits to “small” banks are dissipating.

US credit spreads

The Fed is likely to be the first major central bank to end its normalization. The minutes of the last FOMC meeting indicated that the need for further monetary tightening was“becoming less certain“. This should lead to an upward slope of the curve and a gradual weakening of the dollar over the course of the year. We remain convinced that the US central bank will not cut rates until at least mid-2024, contrary to market expectations. As this state of affairs comes to a head, 5-10 year yields should rise (by 50 basis points). Flows should continue to be redirected towards investment-grade corporate bonds, whose narrower spreads could cushion some or all of this deterioration in government bonds. As far as high-yield bonds are concerned, selection remains essential. The rise in default rates is set to accelerate during 2023/2024. The high interest rate environment poses a major threat to businesses.

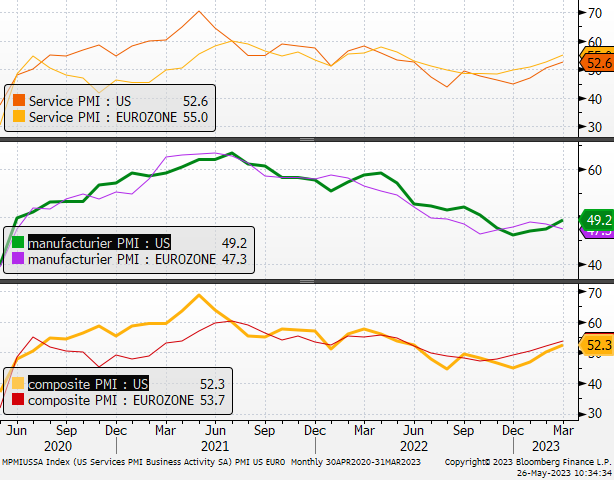

While Europe’s economic momentum remained strong, and despite a sharp drop in energy prices, prospects of an economic slowdown are resurfacing. The risk of a contraction in bank lending prompted investors to favor defensive stocks over cyclicals. A rotation also fuelled by the fall in PMI indicators or the IFO business climate index in Germany, after 6 months of increases, due to the industrial and business outlook components. The momentum of the services sector in Europe, which is still driving growth, is likely to gradually lose steam, leading to below-potential growth in the eurozone over the next few quarters.

Comparison of leading indicators between the United States and the Eurozone

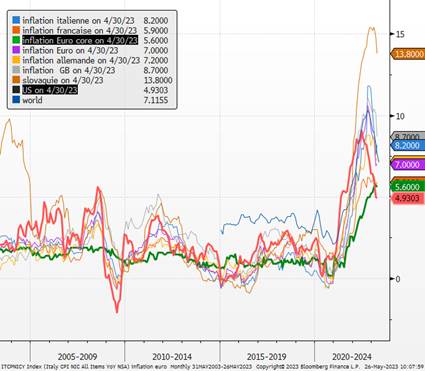

Inflationary pressures should ease, but not enough to halt the monetary tightening cycle. We expect 3 more rate hikes until September. The European Central Bank’s action must now be sustained in the face of persistent inflation. Faced with this situation, it will have to act to counter inflationary pressures driven by services.

Rolling inflation

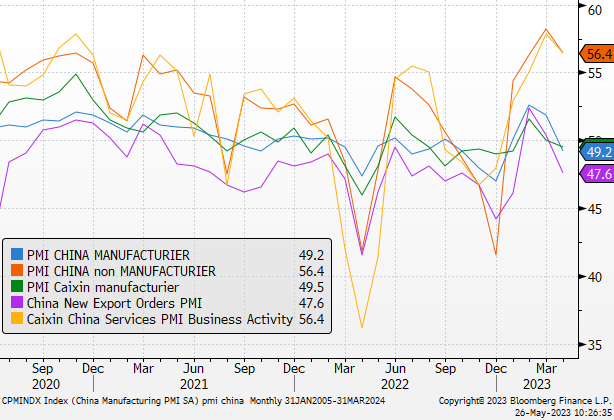

Beyond a particularly strong sequential rebound in Q1-2023, surpassing consensus assumptions, Chinese growth has tended to disappoint in recent weeks. Most indicators, notably those for the manufacturing sector, industrial production, credit and financing, underline China’s current difficulties, despite the reopening initiated at the end of 2022. Weak global demand for goods, the rebalancing of production chains and difficulties in the real estate sector could limit the extent of the growth rebound.

Authorities continue to opt for moderate fiscal and monetary support as long as the major central banks maintain their interest rate normalization, thus avoiding too significant a depreciation of their currencies. Consumption will certainly benefit from the reopening of business, especially as low inflation (against the rest of the world) is boosting the purchasing power of Chinese households, which will support Chinese growth in the second half of the year. As for real estate, the situation has been improving for several months now, but has not served as a lever for growth as in the past.

Forward-looking indicators for the Chinese economy

We remain optimistic about emerging markets, particularly Asia, for the second half of the year. Paradoxically, moderate, non-inflationary growth remains a positive factor for the time being. The negative scenario would have been a start-up that would have pushed all prices up, creating a wave of inflation that would have forced central banks to act much more restrictively. This risk persists, but the likelihood of it materializing is more likely to be at the end of the year or in 2024.

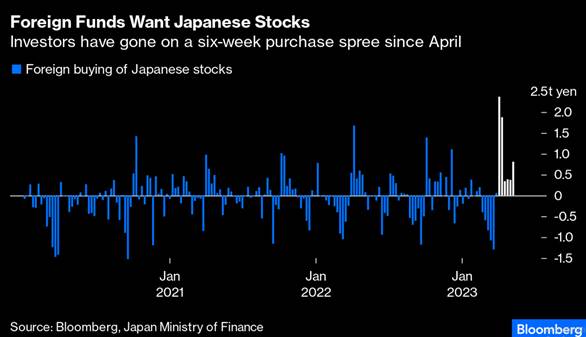

As far as Japan is concerned, the fall in the yen has been a support factor for equities, which have outperformed in recent weeks. The country’s indices have just reached a 30-year high. The country benefits from its new status as a “zone of calm” in Asia, following the reduction in geopolitical risks. What’s more, after years without inflation, Japanese investors were not particularly enthusiastic about the equity market. Japanese households allocate just 10% of their savings to equities, compared with 20% in Europe and 40% in the United States. The economy is recovering, exports are showing solid growth and there are few supply constraints. The reforms called for by Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to establish a “new form of capitalism“In the medium term, these measures should pay off by accelerating the transfer of citizens’ savings (which amount to some US$15,000 billion) into investment, thereby increasing the long-term value of Japanese companies. We take this aspect into account to have a more constructive attitude (neutral positioning).

In the short term, the risk relative to other regions is linked to monetary policy, which is set to tighten from the third quarter onwards due to persistent inflation and a falling currency. This change of course in Japanese monetary policy will put the country at odds with other developed-country central banks, which will pause their monetary tightening. We recommend holding Japanese equities without hedging the currency.

As far as the dollar is concerned, we continue to believe that the euro should appreciate against the dollar. In recent months, the euro-dollar exchange rate has been strongly linked to the spread between short-term interest rates in the United States and Europe. This gap was very wide before the start of the European Central Bank’s rate hike cycle a year ago, but has narrowed steadily since. Recently, offensive statements by some FOMC members and a certain appeasement concerning the regional banks have enabled the dollar to recover, but this is likely to be temporary, as the ECB has to catch up with the Fed, given Christine Lagarde’s persistent determination.

Euro-dollar and credit spread

The risks of our moderately optimistic scenario are twofold: in the short term, if no agreement is reached to raise the US debt ceiling, the markets could experience a very violent downturn. This downturn should be used to reinvest in equities. In the medium term, a resurgence in core inflation would lead to further interest rate hikes and plunge the economy into a deep recession.

CONCLUSION IN TERMS OF ASSET ALLOCATION