Lowering interest rates: the day after?

The big question of the summer is how policymakers can best define monetary policy.

On numerous occasions, central bankers have stated that they would change their interest rate policy only to retract later. It would be more appropriate to be clear about the risks they are taking…

Between the United States and Europe, the available data, which should help make a decision, is very different.

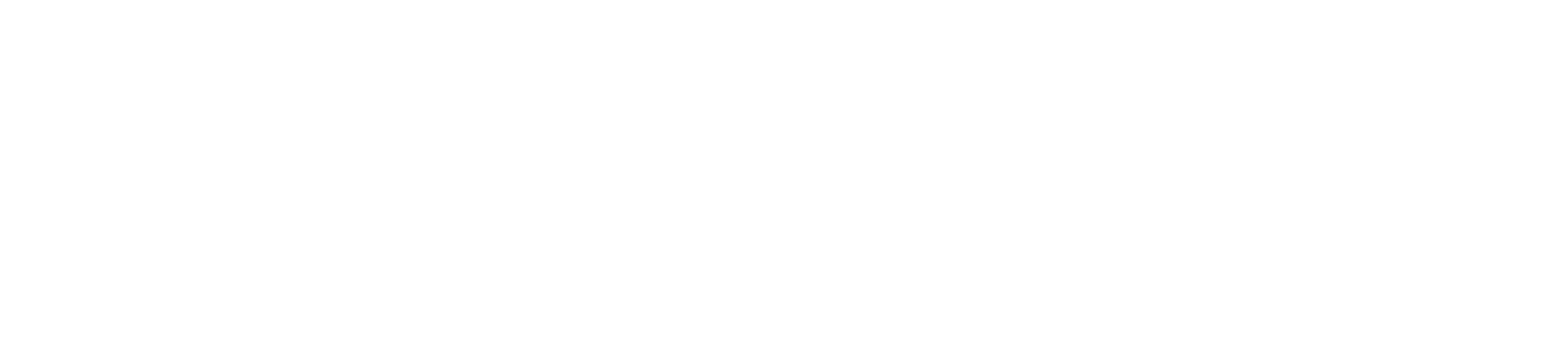

Real Growth: US vs. Euro Zone

In the United States, strong domestic demand has been the catalyst for the inflation shock. In Europe, it is the supply shock (due to the surge in heating and electricity costs following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine). Savings rates remain high, posing the threat of insufficient demand. We have previously described this phenomenon extensively, but this difference inherently implies a decoupled monetary action.

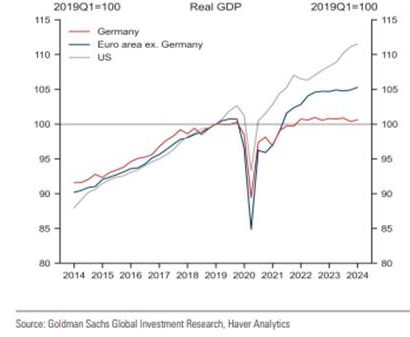

This differentiation is also evident at the state level regarding fiscal stimulus. While deficits are lower and expected to decrease further in Europe, they are likely to remain high in the United States. With such a divergent stance between the American and European economies, risk assessment should also be radically different.

Is it really serious if central banks make a mistake by lowering interest rates?

Central bankers tend to assert that they want to be in a series of interest rate movements—either up or down—without having to change their minds. This has several implications: they may sometimes wait too long to be certain or, conversely, may not reverse their decision in the case of a clear mistake. They aim to establish their actions over a relatively long period. However, in a way, the only thing that truly matters remains the real activity and the lives of businesses and households.

To their credit (and what we are experiencing is indisputable proof), the actions of monetary policy take time to fully impact the economy. Given the diversity of transmission mechanisms, the effects of changes in key interest rates only materialize after long and variable delays.

Housing is an important vector of monetary policy transmission. Mortgages are the main financial commitment for households, and housing often constitutes the bulk of their wealth. Real estate also represents a large share of consumption, investment, employment, and consumer prices in most countries. Monetary policy has more significant effects on activity in countries where the share of fixed-rate mortgages is low and where household debt is high.

Jerome Powell, the chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, has often mentioned the lag between monetary policy actions and their effects on the economy. In December 2023, he reminded us that monetary policy affects the economy with a delay and that the full effects of tightening have probably not yet been felt. Generally, economists and central bankers estimate that monetary policy has a delayed effect, often between 12 to 18 months, with the first rate hike occurring in March 2022.

Fed Rates vs. Inflation

Sources : Bloomberg, Richelieu Group

In the formal discourse of monetary authorities, the worst-case scenario would be to start a series of interest rate movements and then change course, however this carries little cost to society. If they follow the path of being absolutely certain (high confidence, as often cited by J. Powell) before making a rate change decision, they ensure that rate movements will be delayed, causing real costs to others.

If they enter a sequence of rate cuts too evidently, the markets will adapt very, if not too, quickly. Imagine Jerome Powell or Christine Lagarde announcing a regular series of rate cuts for 2024 and 2025. Interest rates would rapidly adjust, creating a dynamic of expansion in credit distribution, an increase in demand, and a dangerous inflationary wave that would later need to be curbed by even more restrictive measures than before.

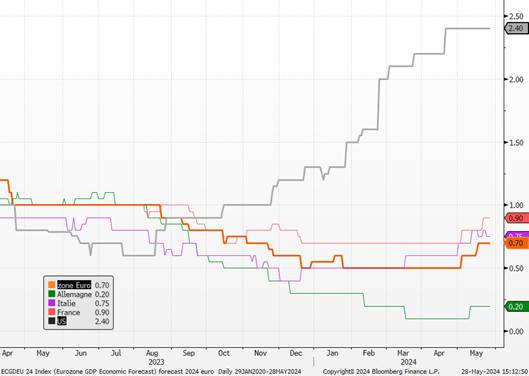

To what extent and at what pace should interest rates be reduced?

In the United States and Europe, the question is how much and how quickly to reduce interest rates. On one hand, acting too aggressively risks generating unsustainable demand, leading to another wave of inflation; on the other hand, a too restrictive policy could trigger systemic risks for some of the most fragile actors and bring a risk of deflation, which would force a return to unconventional policies.

In the United States, the Fed needs to feel more comfortable with disinflation before it can ease the pressure it is exerting. There is little sign of a significant economic slowdown in the short term, and the latest inflation data, although a relief, has not provided much assurance that inflation is stabilizing near the 2% target. If enough evidence shows that inflation is decreasing, the Fed can ease monetary policy with little risk, but there is also little danger in waiting until the fall.

US Leading Indicators

Sources : Bloomberg, Richelieu Group

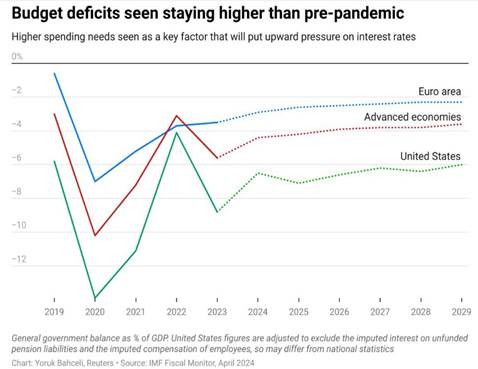

Europe needs stimulation. Inflation has been steadily decreasing, and according to forecasts, wage pressures in the eurozone are also decreasing as expected. The main risk in Europe is that monetary policy remains too strict and compromises the necessary recovery in demand towards pre-pandemic trends. The ECB should follow the example of Sweden and Switzerland and begin a rate-cutting program. It has indicated that it will take the first step in a few weeks. It would be wise to continue after this initial step.

Historical Bloomberg Estimates of Economic Growth for 2024

Sources : Bloomberg, Richelieu Group

The ECB should embark on a series of rate cuts and provide visibility. Conversely, the Fed must strike a balance between expectations of rate cuts and fears of a less accommodative stance to avoid actions that would create conditions conducive to another wave of inflation. The latter should create a permanent doubt about the possibility of a rate hike.

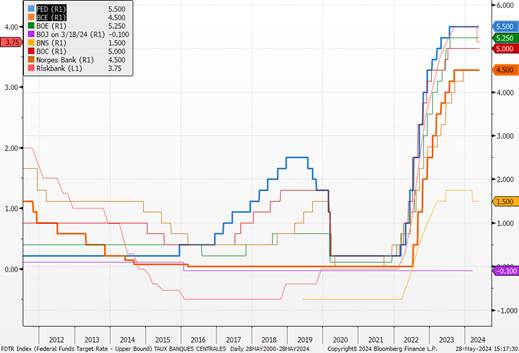

Interest Rates of Major Central Banks

Sources : Bloomberg, Richelieu Group

While history has shown that the ECB and the Fed often operate in tandem, there is no reason this time for the ECB not to act independently from governments and the Fed.