September 22, 1985, New York. In the plush lounges of the Plaza Hotel, five major economic powers sign an agreement that will leave a lasting mark on international monetary history. Objective: to bring down a dollar that had become too strong, posing a real threat to the global economy. This “Plaza Accord,” unique in its kind, seals a rare coordination of exchange rate policies between the United States, Japan, West Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. The context is tense: an overvalued dollar and global trade under pressure.

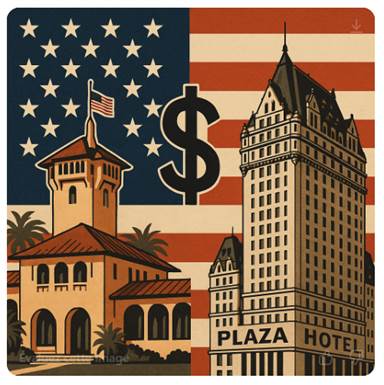

Since the early 1980s, the greenback has soared, gaining more than 50% against major currencies. The cause: the highly restrictive monetary policy of Paul Volcker, head of the Fed, who raised U.S. interest rates to historic levels to curb inflation. Attracted by these high returns, capital flowed into the United States, boosting the currency. But the strength of the dollar turned toxic: American products became prohibitively expensive abroad, the trade deficit widened, and exports plummeted. Factory closures multiplied, especially in the face of Japanese competition, and Washington brandished the threat of new tariffs.

It is in this context that James Baker, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, takes the initiative. He gathers his counterparts from Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom in New York. Objectif : envoyer un signal clair aux marchés : le dollar est trop fort, il doit baisser. Les signataires publient une déclaration commune affirmant leur volonté de corriger les déséquilibres monétaires et, surtout, s’engagent à intervenir de manière coordonnée sur les marchés des changes.

The central banks buy yen, marks, francs… and sell dollars on a large scale. The effects are immediate. Within two years, the dollar plunges: from 240 to 150 yen, from 3.45 to 1.80 marks, a drop of nearly 40% against major currencies.The mechanism proves highly effective: real interventions are accompanied by a sharp shift in market expectations. At the same time, countries commit to adjusting their economic policies: reducing the budget deficit in the United States, stimulating domestic demand in Japan and Germany.

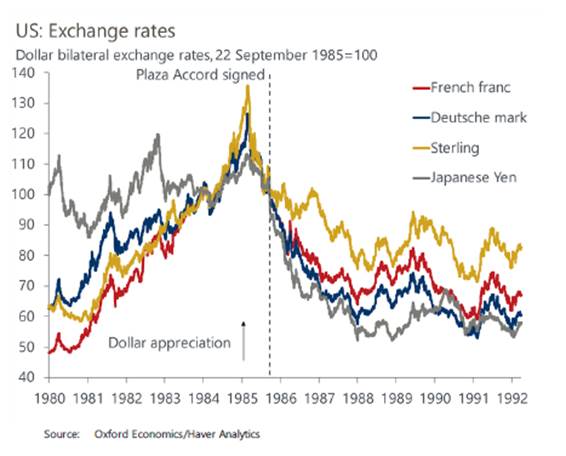

In the United States, the Plaza Accord relieves the export industry and helps improve the trade balance; however, the effect remains partial and budgetary excesses persist. Japan, for its part, pays a high price: the appreciation of the yen weakens its exports. To compensate, the Bank of Japan eases its monetary policy. The result: an unprecedented real estate and stock market bubble, which bursts at the end of the 1980s, plunging the country into a decade of stagnation. Germany weathers the episode better, supported by strong domestic demand. As for France and the United Kingdom, their lesser economic weight positions them more as spectators than leaders.

U.S. deficit as a percentage of GDP

Le Plaza Accord reste à ce jour l’un des rares exemples de coordination monétaire internationale réussie. Il fut suivi en 1987 du Louvre Accord, cette fois pour stabiliser les taux de change, la baisse du dollar étant jugée suffisante.

The Plaza Accord remains to this day one of the few examples of successful international monetary coordination. It was followed in 1987 by the Louvre Accord, this time aimed at stabilizing exchange rates, as the decline of the dollar was deemed sufficient.

The historical precedent set by the Plaza Accord could actually be a significant obstacle to the renewal of such an agreement.

The event was highly favorable to the Americans and devastating for the Japanese. China is certainly aware of this: it will not yield easily. Moreover, unlike Japan, which sought above all to ease geopolitical tensions in the 1980s, China today embraces its role as a rival and is ready to engage in an economic war if necessary. The Middle Kingdom is not seeking consensus at any cost. Its guiding principle remains achieving leadership in new industrial and digital technologies.

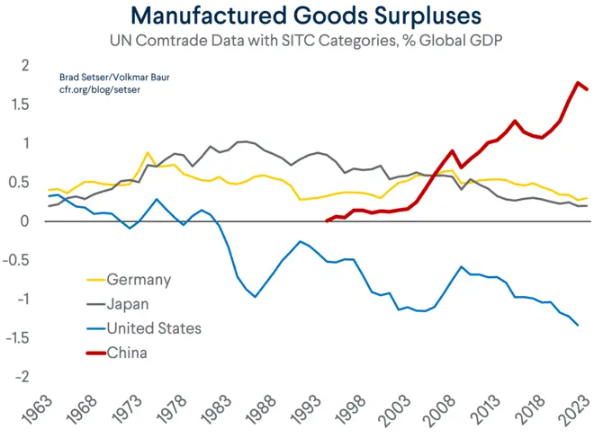

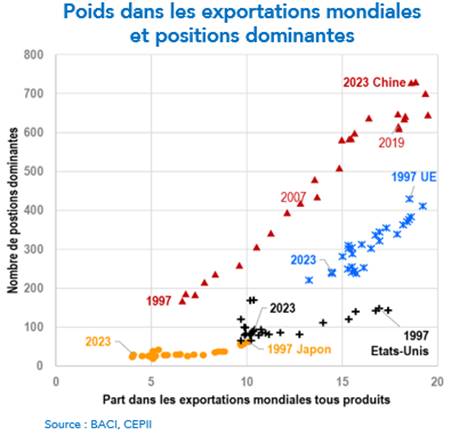

It is also worth mentioning that the Japanese, still traumatized by the events of 1945, were militarily fearful of the Americans in the 1980s. In contrast, China is striving to match the United States by massively investing in defense. On the commercial front, the challenges posed by China are significantly greater than those generated by Japan in the 1980s. Firstly, the scale of China’s trade surplus reached nearly 2% of global GDP in 2024, compared to Japan’s 1% at best in 1985. Even more striking, since the late 1990s, China has seen an explosion in the number of its dominant market positions, defined as products for which its share of global exports exceeds 50%. China held a dominant position in 730 industrial products in 2023 (about 15% of the product lines recorded in the BACI database), compared to 238 for the European Union, 94 for the United States, and 30 for Japan. Finally, China’s dominant positions are concentrated upstream in value chains (metals, rare earths, minerals, basic chemicals, etc.), whereas Japan was mainly developed in intermediate and finished goods industries. China’s ability to control the production of industrial inputs makes it formidable, as export restrictions could lead directly to production shutdowns.

Would a new “Plaza Accord” then be possible under current conditions? Why would Beijing, Brussels, and Tokyo have an interest in letting their currencies rise against the dollar?

Forty years after the Plaza Accord, the idea of a common monetary front to ease trade tensions is resurfacing. At the time, Washington had convinced Tokyo, Bonn, Paris, and London. Today, the same logic is appealing for a simple reason: a strong dollar fuels the tariffs imposed by the United States, while a stronger local currency could mechanically make them less necessary.

For China, this would offer a way out of the tariff deadlock. A stronger yuan would provide Beijing with a concrete concession to Washington: less competitive advantage, and thus less reason to impose punitive taxes.

Moreover, a more expensive currency strengthens domestic purchasing power and accelerates the already initiated transition toward domestic consumption and technological upgrading, helping to rebalance the growth model. The risk could be a short-term shock for the traditional export industry, but the Chinese government has fiscal tools at its disposal to cushion the blow.

For Europe, it would be a tempting anti-inflation move. In the face of soaring energy prices, a stronger euro is the best shock absorber: it would lighten the energy bill—crucial for Germany and Italy—and anchor inflation expectations in a region where the ECB is struggling to bring the price index below 3%. It would also help attract new external capital.

Admittedly, the aerospace industry, German automakers, and French luxury goods sector would lose a few margin points; but Brussels could negotiate, in exchange, the lifting of surcharges on steel, aluminum, or European electric vehicles.

For Tokyo, the scars may still be visible: after 1985, the yen had surged… and the real estate bubble with it. Yet, a strong currency would reduce the cost of liquefied natural gas and oil—Japan’s Achilles’ heels—while strengthening household purchasing power, essential to revive still sluggish consumption. A concession on exchange rates would also solidify the relationship with Washington, a security cornerstone against China.

Granted, the Bank of Japan still fears deflation, but after two years of inflation close to 2%, the ground is less treacherous than it was a decade ago.

What the United States would gain is clear. We would see a reduction in the trade deficit without endlessly multiplying tariff barriers, a revival of “Made in USA” exports in aeronautics, agriculture, intermediate goods, and, of course, a moderation of the domestic price hikes linked to tariffs (the duties paid on imports ultimately add to business and consumer costs). Imported inflation could be offset by controlled oil prices.

For now, tensions between countries remain high; isolationist pressures are emerging on all sides. Washington would need to agree to reduce tariffs, provided there is coordinated action on exchange rates, while Beijing, Brussels, and Tokyo would likely prefer this path over a chronic trade confrontation.

The geopolitical situation may not be ideal, but the threat of a global recession and the escalation of a trade war from which no one would emerge unscathed could act as a catalyst.

Interests could converge: reducing tariffs without wrecking growth. Obstacles as well: strategic rivalries, internal resistance from export sectors, and Japan’s painful memories of the 1990s. Thus, a new Plaza Accord would only be born under the pressure of a major trade crisis. Trade imbalances have not completely disappeared, and national economic policies often remain divergent.

As for the side effects, like the Japanese crisis, they serve as a reminder that manipulating currencies is never a neutral act. While history never repeats itself exactly, it often rhymes: 1985 could very well shed light on 2025.

Given the current situation between China and Donald Trump, a solution of this kind remains unlikely in the short term. The situation is more complex, but the relationship between the players is even more so.

An intermediate solution could be a combination of tariffs on China and currency agreements with other countries.

If a remake of the Plaza Accord were to emerge in America in 2025, it would be natural for commentators and markets to label it the “Mar-a-Lago Accord,” both to respect the tradition of naming it after the place of signature and to highlight Donald Trump’s enduring imprint on American trade diplomacy.

In 1985, the “Plaza Accord” simply took its name from the Plaza Hotel in New York, where the G5 finance ministers met. If a new multilateral monetary agreement were signed at the Mar-a-Lago club-resort, it would follow the same toponymic logic.

Mar-a-Lago is the private residence of the former American president, often referred to as his “Winter White House” since he turned it into a club in 1995. Choosing this site would symbolically anchor the agreement in the continuity of the economic diplomacy initiated under Trump, who remains highly influential in the debate over trade and the dollar. The complex hosted the first summit between Donald Trump and Xi Jinping in April 2017, illustrating its capacity to host high-level negotiations between major powers. Ironically, the Plaza Hotel was briefly owned… by Donald Trump in the late 1980s.